A founder after fondue’s own heart

The man behind France’s first cheese museum shares his expertise about the history and singularity of French cheese.

Scheduling an interview across time zones is easier said than done. Scheduling an interview across time zones with someone who is the official cheese and wine tasting supervisor of the summer 2024 Paris Olympics — well, forget it.

But if there’s one thing Musée du fromage’s Pierre Brisson will always make time for, it’s cheese: serving it, talking about it, making it — his life revolves around the product, and that includes carving time out for an interview with a burgeoning dairy expert (me).

When I spoke to Brisson, it was over a 12 a.m. Central Standard Time video call. Brisson came into the frame with a wide grin; he was enjoying a brisk, sun-filled morning in the garden of his home outside of Paris.

Within the first twenty seconds of bon soir’s and bonjour’s, I knew him to be a man of singular enthusiasm. He spoke of cheese the way one might hail their pure-blooded Labrador or tout a Yale-bound nephew. He spoke of cheese as if it were the most delightful part of his life. And, lucky for us, it is.

Brisson began his French cuisine quest as a vigneron, or winemaker, and later developed an affinity for cheesemaking. Upon entering the field, he noticed a gap in public education about the cheesemaking craft, specifically about French cheese’s storied history and regional departures.

Because France is so unique a country in that it contains a myriad of climates (oceanic, continental, mountain, and Mediterranean), the kind of cheeses that are produced from north to south and east to west are magnificently varied.

“The diversity of climates was a challenge for early cheesemakers,” Brisson said. “But it made possible many different kinds, the kinds we have today.”

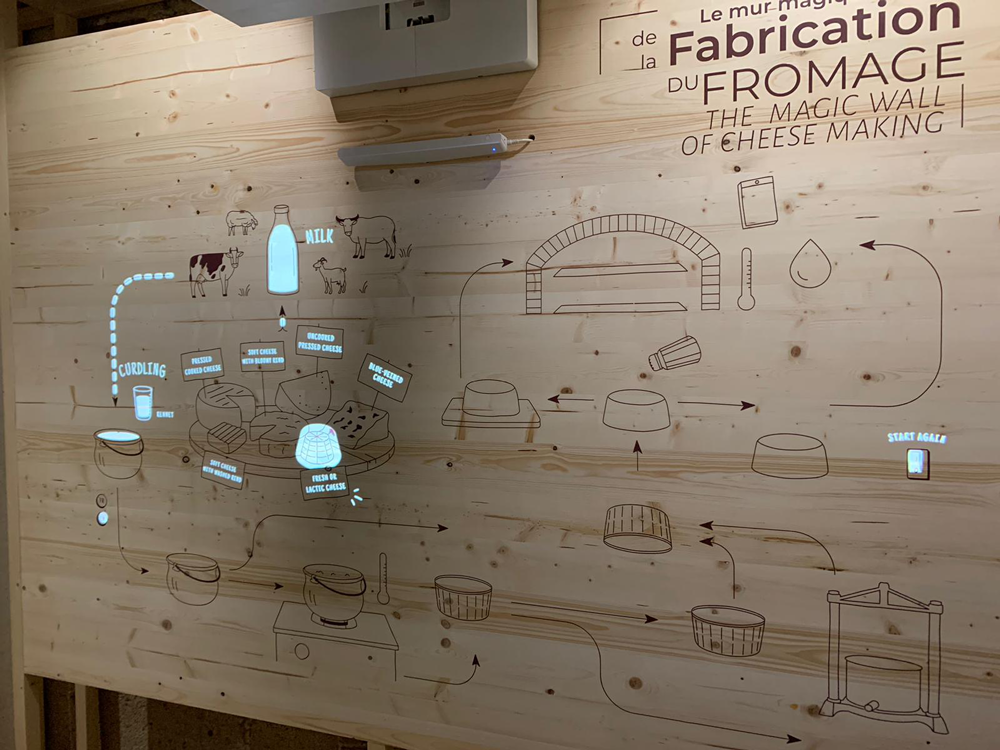

Musée du fromage (France’s first-ever museum dedicated to the history and making of French cheese, created and run by Brisson) details this early cheesemaking trial and error in its exhibition room.

It all started with fifth-century monasteries. The monks needed a substitute for contraband meat — something that provided comparable nutrition. Curdled milk, with its high protein content, became a popular alternative.

“They recorded their recipes for cheese in documents passed between monasteries,” Brisson said. He has visited some of these monasteries himself. “In the original documents, you can see that the type of cheese depended on the ideal way to make it in the different climates where the monks lived.”

For instance, he continued, “In a flat region, where people could travel easily, it was ideal to make and sell wet cheese. They could sell the strained water, too. In the mountains, where travel is difficult, it made sense to strain the curd and make a hard cheese, which would preserve well.”

Brisson and Musée du fromage honor these early French cheesemakers by showcasing cheese that is made by producers who have the craft’s integrity and the product’s purity in mind.

The combined efforts of educators like Brisson and farmers like the ones whose cheese occupies a tray at the museum mean a future for the profession that sees continued respect for over 500 years of artisanship.

See the result of this history-making museum’s launch for yourself on the (once pasture-covered and thus “Cow Island” dubbed) Île Saint-Louis in le coeur de Paris, or opt for ordering equally lauded American-made cheese at www.hoardscreamery.com.